The U.S. Treasury recently released the December monthly statement, which put us to work crunching the data. Note the Treasury is on an October-September fiscal year. We are using calendar years in our analysis.

Federal Borrowing From The Public

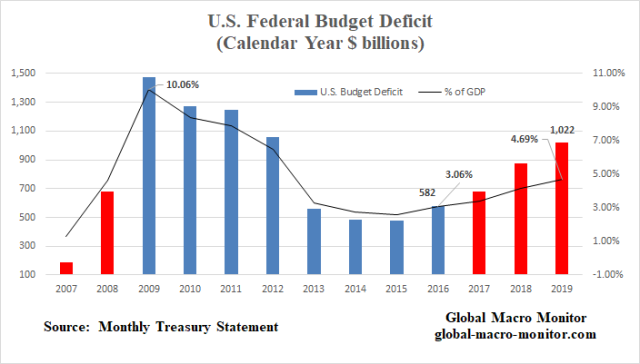

The following chart illustrates the increasing pressure on the private markets given the spike in the U.S. budget deficit, which has almost doubled since 2016 to over $1 trillion in 2019. It is much easier for the Treasury to float a trillion of debt during recessions or risk-off markets as haven flows are starved for riskless assets. Supply is not an issue as demand is overwhelming.

We believe the big spike in borrowing in 2018 crowded out other markets, which put upward pressure on long-term interest rates in September causing the stock market to tumble 20 percent in Q4. The Fed had to ride to the rescue and thus abandon its balance sheet normalization program.

In 2019, the Treasury’s borrowing pressure on the markets continued and forced the Fed to introduce it’s “not QE” policies to help calm the repo and money markets. The long-end of the Treasury market was anchored by yield-seeking record foreign private inflows.

We are not ignoring the issue of why the Fed funds market did not help alleviate the repo rate spikes but just isolating our analysis to collateral supply and will leave the banking issues and analysis up to the experts. At the end of the day, however, nobody really knows for certain what is going on.

The Supply Shock Caused By the Debt Ceiling

We have updated the following chart, which illustrates the “supply shock” caused by the lifting of the debt ceiling in August. From January to July, the Treasury was forced by the debt ceiling to curb its borrowing and financed itself through running down its operating cash at the Fed and by other means, such as running arrears on federal pension funds. Borrowing from the public only increased by a sum total of $113 billion during this seven month period and when the February borrowings are excluded, the Treasury took out a negative $36 billion from the public markets.

After the debt deal was signed in August, the Treasury borrowed almost $1 trillion from the public in the last five months of the year. That is a huge supply shock, folks. Treasury officials are pretty good at managing disruptions to the markets and keeping guard of the yield curve but it does seem the budget beast is getting just too big to tame.

Such a public debt supply shock can partially explain, in our opinion, the repo and money market turmoil and the coincidental timing of both do not go unnoticed.

We don’t know but it is possible the money markets may calm down after the initial shock works through the system. Then, again maybe not. The Fed may be forced to buy a boatload of Bills as central banks used to hold almost 50 percent of all T-Bills outstanding. They now hold only around 15 percent of the much larger stock, adding more pressure on the money markets.

Le Chatelier’s Principle

Another important point is that interest rates are not allowed to move to their market-clearing equilibrium levels, where the supply of loanable funds and capital meets demand for borrowing.

It’s a classic case of Le Chatelier’s principle (LCP) in action. If one economic variable is repressed in a dynamic equilibrium system, such as prices or interest rates and not allowed to adjust to clear the market, another variable in the system will have to move to offset. The great economist, Paul Samuelson, did his Ph.D. dissertation on LCP. – GMM, Sept ’19

No wonder why the money markets are going batshit.

U.S. Budget Deficit

The U.S. budget deficit has almost doubled in the past three years, which is rare during a period of positive GDP growth.

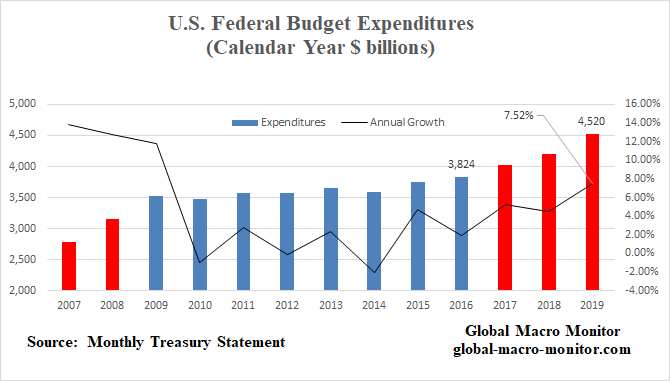

Budget Expenditures

Note total Federal budget expenditures increased by over 7.5 percent in 2019 at a rate not seen since the GFC.

Budget Revenues

What surprised us about this chart was that the absolute level of budget receipts did not retain their 2007 pre-GFC levels until 2013, illustrating how ugly the economic downturn was and it deleterious impact on government revenues. It also shows how recession and the subsequent collapse of budgetary receipts blows up the deficit.

Upshot

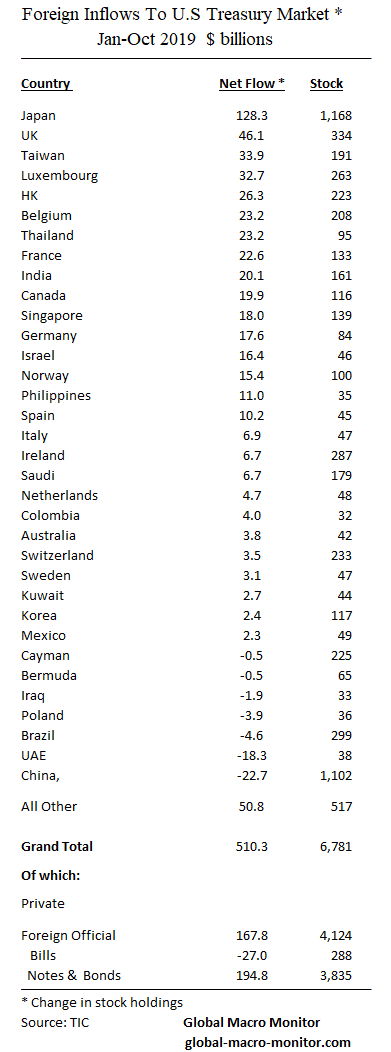

Washington has thrown all semblance of budget discipline to the wind and, in our opinion, will increasingly have to depend on the Fed to help finance its spending without crowding out markets and tanking risk markets. It is important to watch foreign private inflows into the Treasury market, which has already broken the annual record inflow even with only the latest data from October.

The Treasury’s dependence on foreign savings to finance itself keeps a lid on long-term rates. Moreover, private investors are much more sensitive to market pricing than foreign central banks, who make up 61 percent of foreign holders of close to $7 trillion in Treasury securities. The Treasury is becoming more reliant on “hot money” flows.

Based on this analysis, we conclude the two big tail risks to monitor with respect to another public sector financing shock: 1) inflationary pressures, which could take the Fed out of the deficit financing game and spike interest rates, and 2) a reversal of foreign private inflows into the Treasury market, already at a record annual inflow of almost $350 billion as of October, which would put upward pressure on long-term interest rates. The U.S. budget deficit in 2020 will be the equivalent of almost 90 percent of global foreign savings (current account surpluses).

Recession or slowdown fears, however, will bring haven flows into Treasuries and repress interest rates even further.