It was the autumn of 1996 when I arrived in Sofia, Bulgaria. I was working for a major Wall Street investment bank and had a clear and urgent mission to assess the sustainability of Bulgaria’s sovereign debt. The atmosphere in the capital was tense; the economic and political uncertainty hung thick in the air. The government was hanging by a thread while struggling to roll over its maturing Treasury bills. The early signs of a major burst of inflation were no longer subtle, as confidence in the Bulgarian currency was rapidly diminishing. In a series of high-level meetings with senior officials, one stood out: a particularly strained and revealing encounter at the Bulgarian National Bank (BNB), where the full scale of the crisis came into sharp focus.

Central Banker Confession

What I remember most vividly was sitting across from a senior BNB official. When I asked how the government would roll over its large tranches of domestic Treasury bills coming due, he looked me in the eye and said, “Gregor, we will not let the government default.”

Hyperinflation

It was less reassurance than a veiled admission—the central bank would monetize all the debt coming due if need be. At that moment, I knew a currency collapse and hyperinflation were imminent. As soon as I stepped out of the central bank, I called our trading and sales desk in New York to warn that the lev was about to collapse and hyperinflation was coming.

Indeed, within months, monthly inflation hit 242%, and the lev was virtually worthless, losing 90 percent of its value before the country was forced to implement a currency board. I remember buying a bottle of good wine for the equivalent of 27 U.S. cents. During a hyperinflationary spiral, the exchange rate moves first, and domestic prices follow.

Bad Economic Policy

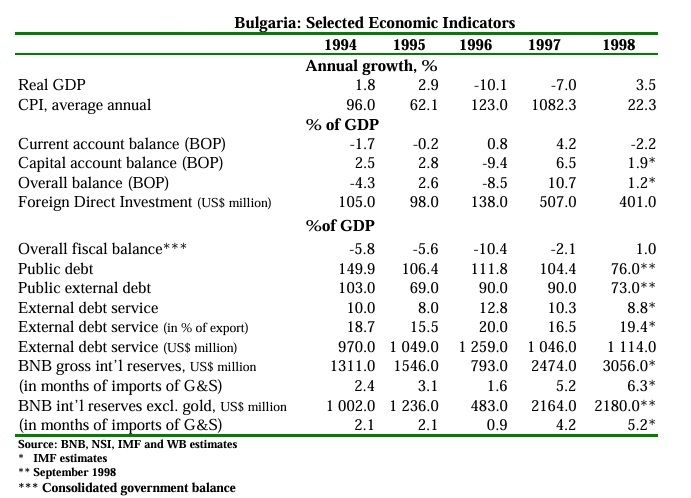

Bulgaria’s crisis was the product of delayed reforms, systemic banking fragility, and most importantly, a collapse of market confidence. After the fall of communism, its banking sector remained riddled with non-performing loans and politically motivated credit issuance. When the government failed to roll over its domestic debt, the central bank was forced to buy unsold Treasury bills, initiating a fatal inflationary spiral. By late 1996, the BNB had monetized nearly the entire public domestic debt, with inflation exploding and currency substitution rampant. There was no functmioning bond market—no buyer of last resort except the printing press.

U.S. Economic Policy

In contrast, during the COVID-19 crisis, the U.S. Federal Reserve engaged in massive Treasury purchases, effectively monetizing the new debt. In the table below, we illustrate how the U.S. government issued almost $5 trillion of new debt to finance the massive COVID deficits. The markets could not absorb such a large new issuance, and the Fed stepped in and took down 91 percent of all net new debt — not through the auctions but indirectly from primary dealers — including 84 percent of all coupon securities and much of the incremental increase in T-bills.

This move, however, did not trigger hyperinflation. Why? Because global confidence in the U.S. dollar remains deeply entrenched. As Ray Dalio, Barry Eichengreen, and other economists note, the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency allows the U.S. to borrow cheaply despite a public debt exceeding 120% of GDP

Fading Confidence

But that privilege appears to be eroding. Recent headlines reveal a sharp sell-off in the dollar, rising Treasury yields, and spiking gold prices not from inflation fears alone, but from doubts and lack of credibility in the U.S. government itself.

If a similar crisis were to hit today, given current market conditions, particularly the falling confidence in U.S. assets, it is questionable whether the Fed could act so aggressively.

The “exorbitant privilege” is now in question. Foreign holders of U.S. Treasuries, possibly China and Japan, appear to be quietly trimming their U.S. debt exposure. The traditional “flight to safety” into Treasuries during crises is faltering. Even safe-haven capital is drifting elsewhere—into German bunds, gold, the Japanese yen, and the Swissie.

Heed the Lesson

Bulgaria’s crisis teaches a painful lesson: when confidence is lost, governments can’t borrow, and central banks must print. That’s not theoretical—it happened. It happened in many of the countries that I worked with, including Argentina, Venezuela, Poland, and Brazil. And while the U.S. is a world apart in size and economic complexity, the fundamental rules of finance still apply. If global investors lose faith in the dollar the way they lose faith in an emerging market, the U.S. will face higher borrowing costs, capital flight, and weakened policy flexibility.

The Congressional Budget Office now warns of “significant fiscal risk” if current debt trends continue. Tariff wars, political instability, and threats to Federal Reserve independence all compound this risk. The next crisis may not grant the U.S. the luxury of borrowing its way out. If that confidence evaporates, we will be staring into the mirror of Bulgaria’s past.

Confidence is Fragile

I’ll leave you with a fitting quote from the GOAT of NFL quarterbacks, Joe Montana:

“Confidence is a very fragile thing.”

Let’s hope the President takes that to heart—and soon.

Pingback: The Anatomy of a Bond and Currency Crisis | Inflation Cafe

Pingback: Fiscal Scorecard: How COVID Torched the Budget | Global Macro Monitor